Wolfgang NÄSER,

Marburg, invited lecture at Tohoku University, Sendai, Japan, on

March 10th, 2006

Wolfgang NÄSER,

Marburg, invited lecture at Tohoku University, Sendai, Japan, on

March 10th, 2006  Wolfgang NÄSER,

Marburg, invited lecture at Tohoku University, Sendai, Japan, on

March 10th, 2006

Wolfgang NÄSER,

Marburg, invited lecture at Tohoku University, Sendai, Japan, on

March 10th, 2006

NB. In May 2010 all former *.ra samples were converted to *.mp3 and can be decoded best with the Windows Media Player

The German dialects or Mundarten

are as old as interesting. They are vivid and colourful, powerful

and expressive and can produce all sorts of utterances, be it

grief or joy, humour and the philosophy of life. A hundred years

ago there was the saying that German dialects were dying out but

they have remained alive and active. To begin with a first sample:

(Student) Last December Í ran into a

24-old student of English and German philology who spoke into my

microphone:

This is Central Hessian dialect which, up to now, can be heard in many places around Marburg and Giessen.

The world of German dialects is a little universe of its own. Around 100.000 questionaires, 1.600 hand-painted maps, several thousands of indexed audio samples and other materials (the new digitized ones included) can be found in the archives of the Deutsche Sprachatlas in Marburg. Even my modest little archives contain so many recorded samples and other stuff that I would fail to remember all I gathered up to the present day. Here, in the Center of Excellence, I will confine myself to what may be an essence of working with dialects. As a philologist I look at them as whole entities, as forms of artistic variation, of enriching language power so I would not be very fond of the so-called deficit hypothesis of the last 60's. I chose to work on dialects because in my view they are no restricted codes and because I think that all these elaborated variants are not only perfectionized media of communication but can also serve as forms of art. So let me give to you some of my very personal views on dialects, finally presenting some of them to be experienced in an acoustical way, just as the blind people do because they don't have any other sense of decoding messages of that kind.

What is a dialect?

There

were many attempts to describe and define the rise and nature of

German Mundarten. Numerous articles and even monographs

were written on dialect theory. As soon as structural

linguistics had discovered them dialects turned to be exotic

creatures worth being treated in a very special scientific way

comprising abstraction and modeling of all sorts,

not taking into account that a dialect can be understood and

detected only when it sounds, when it is acoustically perceived.

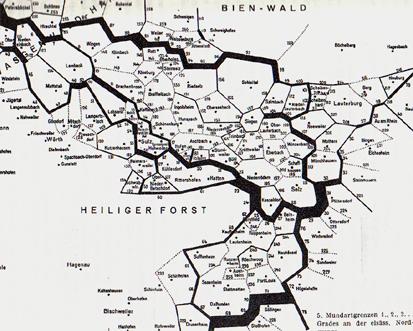

In the 19th century dialects were normally classified in a paradigmatic

way, i.e. with regard to phonetics, morphology and

sometimes syntax; as a result, a lot of Ortsgrammatiken

(local grammars) were published. On top of that Ferdinand Wrede

created his most sophisticated Einteilung (classification)

of the German dialects. Dialect boundaries were described

as bundles of isoglosses, dialect areas as honeycomb-like

structures (see right). The influences and modifications of

dialects were put in military terms thus trying to make these

phenomena understandable. But, notwithstanding all these efforts

of sophistication, it is the speaker himself who, without

any scientific knowledge, is so perfectly able to decode a dialect

and to differentiate it from that of the neighbouring village.

Why is he able to do so? Because, since his first steps of

language acquisition, he has internalized the mechanisms and the

lexicon of his mother-tongue and he is thus capable of producing

(encoding) and decoding it in an automatic or non-reflecting

way, including most sophisticated semantic structures in the

concrete and abstract lexical fields.

There

were many attempts to describe and define the rise and nature of

German Mundarten. Numerous articles and even monographs

were written on dialect theory. As soon as structural

linguistics had discovered them dialects turned to be exotic

creatures worth being treated in a very special scientific way

comprising abstraction and modeling of all sorts,

not taking into account that a dialect can be understood and

detected only when it sounds, when it is acoustically perceived.

In the 19th century dialects were normally classified in a paradigmatic

way, i.e. with regard to phonetics, morphology and

sometimes syntax; as a result, a lot of Ortsgrammatiken

(local grammars) were published. On top of that Ferdinand Wrede

created his most sophisticated Einteilung (classification)

of the German dialects. Dialect boundaries were described

as bundles of isoglosses, dialect areas as honeycomb-like

structures (see right). The influences and modifications of

dialects were put in military terms thus trying to make these

phenomena understandable. But, notwithstanding all these efforts

of sophistication, it is the speaker himself who, without

any scientific knowledge, is so perfectly able to decode a dialect

and to differentiate it from that of the neighbouring village.

Why is he able to do so? Because, since his first steps of

language acquisition, he has internalized the mechanisms and the

lexicon of his mother-tongue and he is thus capable of producing

(encoding) and decoding it in an automatic or non-reflecting

way, including most sophisticated semantic structures in the

concrete and abstract lexical fields.

Linguists and philologists have been trying to define dialect and, with that, to differentiate between dialect and standard; here are some quotations. In his Foundations of studying German Linguistics (part 1) Bernhard Sowinski seems to give one of the best and most precise definitions (translation by me):

"Dialect is a mode of utterance

- which always precedes written language,

- which includes local and oral communication on practical daily life,

- which is the normative result of influences from neighbouring communities and linguistic standard and

- which is practiced by a huge number of patriot speakers in certain situations."

[Mundart ist stets eine "der Schriftsprache vorangehende, örtlich gebundene, auf mündliche Realisierung bedachte und vor allem die natürlichen alltäglichen Lebensbereiche einbeziehende Redeweise, die nach eigenen, im Verlaufe der Geschichte durch nachbarmundartliche und hochsprachliche Einflüsse entwickelten Sprachnormen von einem großen heimatgebundenen Personenkreis in bestimmten Sprechsituationen gesprochen wird".]

But, as you know, dialect is not always dialect. "You have dialects, we have accents", a London city guide tells me in the spring of 1988; that sounds a bit too simple; there are urban dialects and regional variants, e.g. the Yorkshire dialects which we know from James Herriot's "All Creatures Great and Small" and the Scottish, Irish and Australian vernaculars, and we have English dialect atlases accordingly.

Only a few languages seem to have such a variety of dialects as Germany has. Up to the present day they have remained present in the mass media, there are dialect theatre performances in many places; there is a dialect newscast in at least one of the official German radio stations, namely Radio Bremen, whereas the Norddeutsche Rundfunk is known for its entertainment program Wi snackt Platt which, on their website, is described as follows (translations by me):

"Siet 1993 gifft dat al uns Sendung "Wi snackt Platt" mit Geschichten von uns bekannten Schrievers as Ina Müller, Reimer Bull, Wolfgang Sieg un all de annern. Denn gifft dat overs ook jümmers wedder een plattdüütschen Klönsnack mit Lüüd, de uns wat ut ehr Leven to vertellen hefft: Schauspelers, Politikers, Handwarker, Buurn oder Seelüüd. Un denn sünd wi all söß Weken in´t Ohnsorg-Theater, wenn dor wedder een Premiere ansteiht. Dor gifft dat plattdüütsche Musik to von Gruppen as Godewind, Speelwark oder de Liekedeler, von Jochen Wiegandt, Lars & Dixi un Knut Kiesewetter." "Seit 1993 gibt es unsere Sendung "Wir sprechen Platt" mit Geschichten von unseren bekannten Autoren wie Ina Müller, Reimer Bull, Wolfgang Sieg und anderen. Dann gibt es vor allem auch immer wieder ein plattdeutsches Gespräch mit Leuten, die uns was aus ihrem Leben zu erzählen haben: Schauspielern, Politikern, Handwerkern, Bauern oder Seeleuten. Und dann sind wir alle sechs Wochen im Ohnsorg-Theater, wenn dort wieder eine Premiere ansteht. Dazu gibt es dort plattdeutsche Musik von Gruppen wie Godewind, Speelwark oder de Liekedeler, von Jochen Wiegandt, Lars & Dixi und Knut Kiesewetter." "Since 1993 there is our program "We speak dialect" with stories of our well-known authors such as Ina Muller, Reimer Bull, Wolfgang Sieg and others. Then, above all, there is our regular Platt German talk with people who have something to tell about their lives: actors, politicians, craftsmen, farmers or sailors. And every sixth week we are in the Ohnsorg theatre when a play has its opening night. There you can listen to Platt German groups such as Godewind, Speelwark or the Liekedeler, Jochen Wiegandt, Lars & Dixi and Knut Kiesewetter."

The

Rise of German Mundarten

The

Rise of German Mundarten

As for the development of the German dialects there are several theories. What we definitely know is that in the 6th century after Christ we have the first written inscriptions (on the spear blade of Wurmlingen, ca. 600, and the sword of Hailfingen, ca. 650) showing the so-called Second Sound Shift. This sound shift filtered German as an individual language or, as linguists said, dialect out of what is called the Germanic branch of the Indo-European family.

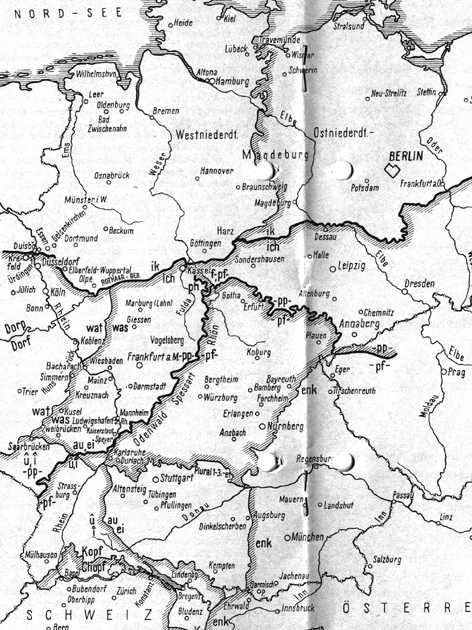

Let us look at our left-hand map which you can find in the Internet. The second sound shift

means that the consonants /p/, /t/ and /k/ as in engl. pipe,

tide, cake were converted to fricatives, namely /f/,

/s/ and /ch/ as in germ. offen, beißen, Kuchen

(for open, bite, cake) or affricates,

namely /pf/, /ts/ and /kch/ as in germ. Pfeife, Zeit

and Swiss German K-chu-e 'cow' or dank-che 'thank

you'. The sound shift started in the south and, like a tidle wave,

weakened on its way north until it ended in the sand. That means:

in the southern zone (Oberdeutsch, Upper

German: dark grey) we have a complete change towards

fricatives or affricates in all positions (front, mid, end)

whereas in the centre (Mitteldeutsch, Central

German: north of the blue Main line) there is only

partial change, e.g. in pepper > Peffer

where we have p > pf in mid position. A very good example of

this mixed development is Ripuarian,

the vernacular spoken in Cologne and its surroundings which

you know very well from the famous Cologne carnival or,

as the native people say, Fastelovend. People there say that

Kölsch is the only language you can drink, for Kölsch is

also a special sort of beer

produced in that region. In "et kütt" ('es

kommt' = it happens) et (engl. it) represents Low

German phonation, whereas in verzellen '(to

tell) we find the characteristic HG sound shift. Kölsch

is closely related to English which you can see or

better hear in hallef for 'half' and other cases (see the

Buuredanz and below).

In the northern zone Niederdeutsch (Low German;

north of the red Benrath line) is

spoken with 'true Germanic' phonation. Low German sounds

seem to be closely related to Dutch, the neighbouring

language of the Netherlands, Vlaams, one of the Belgian

vernaculars, and English as far as its genuine germanic

lexicon is concerned and the Norman heritage is excluded.

The second sound shift finished at around 1400, that is at the

beginning of Early New High German. Of course there is no

evidence with regard to how variants were articulated at that

time. We have, however, written sources in the form of Old and

Middle High German poetry and documents, the Urkunden; there

are certain rhyme structures and analogies permitting

conclusions on how certain syllables were pronounced.

These two maps (left and

centre) show the 4 main regions (north, central west, central east,

south) and the main boundaries (isoglosses) of German

dialects. The Uerdingen ik/ich line separates Low German

from the Central zone (Mitteldeutsch, central

German); south of pp/pf Upper German (Oberdeutsch)

begins; east of Nuremberg-Augsburg-Kempten they say enk (for

'euch', the accusative of the 2nd person plur.) which is Bavarian

(Bairisch).West of this boundary you find East Franconian (Ostfränkisch) in the North

and, in the "sym-badische

Kontinent", the Southern Franconian, Swabian and Alemannic

dialects; south of Kopf/Chopf there are the Swiss German

variants. You find another very nice map here.

These two maps (left and

centre) show the 4 main regions (north, central west, central east,

south) and the main boundaries (isoglosses) of German

dialects. The Uerdingen ik/ich line separates Low German

from the Central zone (Mitteldeutsch, central

German); south of pp/pf Upper German (Oberdeutsch)

begins; east of Nuremberg-Augsburg-Kempten they say enk (for

'euch', the accusative of the 2nd person plur.) which is Bavarian

(Bairisch).West of this boundary you find East Franconian (Ostfränkisch) in the North

and, in the "sym-badische

Kontinent", the Southern Franconian, Swabian and Alemannic

dialects; south of Kopf/Chopf there are the Swiss German

variants. You find another very nice map here.

|

Map No. 4 (left) illustrates

that part of the dialect zones of the former German Reich

now belong to Poland and Russia, with the consequence that

most of the respective ethnic communities have vanished. In

our days, however, counter-tendencies can be observed, such

as in Silesia (Schlesien) which was

German up to 1945 and lost millions of its German

population. Having been reconstructed, Breslau which

is now called Wroclaw

has developed a new sort of cultural self-assurance and identity;

it is common knowledge now that this wonderful town's

history grounds on Polish as well as German roots and that

these two cultures, their language and civilization must

co-exist, must go hand-in-hand so that no kind of hostility

or war can ever emerge in the future.

German standard and / or dialects are still spoken in many foreign countries, e.g. in the former communist countries of Eastern Europe as well as in Northern Italy, France, Belgium, the Netherlands, the USA, Canada, Mexico and Southern America (e.g. Blumenau), whereas, for political reasons, it has nearly vanished in states such as South Africa ("Nataler Deutsch") and Namibia (e.g. Windhoek). |

Naming the dialects

The main German dialects such as Bavarian, Franconian, Swabian were called after those Germanic tribes where they originated. On the other hand there is no general Hessian dialect or language (as Wikipedia states); it is considerably misleading to conclude, as tourists use to do, that the Gebabbel of the Frankfurt region is Hessisch. Hessen (which is the result of an administrative reform) developed 4 main dialects, namely that of Northern Hesse (around the city of Kassel), Central Hesse (including the Marburg and Giessen area), Eastern Hesse (around Fulda) and Southern Hesse (around Darmstadt which is south of Frankfurt). The north-western zone is neighbouring to Westphalia so in certain locations you can find the bruoken forms here, too.

As far as Low German or, as people say, Plattdeutsch is concerned we have a very flat land there indeed; on the other hand, "mir schwäddse Platt" means that you can find the speakers in the central area where Hessian and Palatine dialects (Pfälzisch) are located including those of the Moselle and Saar region. This Platt which is synonym with Dialekt or Mundart derives from Plat Dytsch which means plain German in the sense of simple German. It is interesting that native speakers often call their vernacular (den or das) Dialekt whereas the term Mundart is often used by linguists, just the same with Computer (the general term) and Rechner (used by professionals and / or scientists) ; not until 1969 the well-known Zeitschrift für Mundartforschung (Journal of Dialectology) changed its name to Zs. für Dialektologie und Linguistik when a new approach to dialects was made including computational evaluation.

As the European Linguistic Atlas proves German dialects must be seen in a greater context. There is a slight but constant change from region to region which can be seen when comparing the Dutch, the Low German and the Luxemburgish variants in the northern axis and the respective dialects in the southern direction. This linguistic variety functions as a mirror of ethnic and cultural differences and transitions, which makes Europe a well woven carpet of colourful and artistic patterns of sounds, words and phrases. So we can say that the "old Europe", as Donald Rumsfeld contemptuously called it, owns this linguistic variety as one of its most valuable treasures and that, furthermore, it is one of our most eminent tasks to preserve and to guard our languages and their variants with care and respect (Lit.: Peter Auer (ed.): Dialect change: convergence and divergence in European languages. Cambridge 2005)

Dialect versus Norm: the Emergence of the German Allgemeinsprache

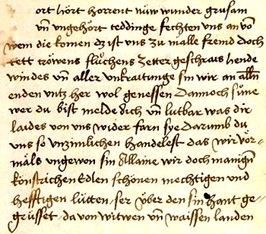

In the OHG period the first written dialects came into being;

later on these written variants were to play an enormous

role in the quest for developing a German standard.  The Urkundensprache

at the court of emperor Karl IV., Johann v. Tepl's "Ackermann aus Böhmen" (> 1400, see right)

and the texts of German mysticism mark the first steps

towards a generally accepted Allgemeinsprache capable of

abstracting, of philosophizing and of forming scientific

hypotheses.

The Urkundensprache

at the court of emperor Karl IV., Johann v. Tepl's "Ackermann aus Böhmen" (> 1400, see right)

and the texts of German mysticism mark the first steps

towards a generally accepted Allgemeinsprache capable of

abstracting, of philosophizing and of forming scientific

hypotheses.

Our modern German Standardsprache or, as Mirra

Guchman would say, deutsche Nationalsprache, was born by

accident. You know the Deutsche

Hanse; this trading organization was founded in the 13th

century and went down at around 1500. The Hanse bureaus covered an

area reaching from London to Nowgorod. The official Hanse language

was Middle Low German which then spread to the

center of Germany as we know from ancient documents (Urkunden).

Had MLG become normative we would nowadays speak a sort of Dutch

and say Goeie Dag to each other; but, when the Hanse went

down in the 15th century, Middle Low German disappeared as written

language and remained only in the North where Low German or Plattdeutsch has been

used to the present day. In the 16th century the Upper Saxon Kanzleisprache became

dominant. From 1516 on Martin Luther's (1483-1546) texts were

printed in German; in 1522 he translated the New Testament,

the problems of this work were dealt with in his "Sendbrieff vom Dolmetschen"

which appeared in 1530. His Bible translation (see here) had a mighty effect

on people all over Germany because here you could find powerful

words and phrases which found their way into people's hearts. Here

are some examples of his innovative vocabulary (translations by

me):

anschnauben (snort at), auserwählt (chosen), Blutgeld (blood money), Dachrinne (gutter), durchsäuert (totally sour), Eifergeist (zealot), einpfropfen (graft), ernten (harvest), sich erregen (get annoyed), Feuereifer (enthusiasm, zest), Feuerofen (furnace), Flattergeist (waverer), Fleischtopf (meat pot, symbol of good life), die Friedfertigen (the peacemakers), gastfrei (hospitable), gottselig (blessed in God), (nach) Herzenslust (to one's heart's content), die Hohen Priester (the High Priests), Ihr Kleingläubigen (Oh you faint-hearted ones; 'o ye of little faith'), Kriegsknecht (mercenary), Lästerlippen (malicious tongues, blasphemists), Landpfleger (governor), Linsengericht (lentil dish, mess of potage), Menschenfischer (fishers of men, Mt. 4,19), Morgenland (orient), nacheifern (emulate, imitate), nachjagen (pursue, chase after), ihr Otterngezücht (adders' breed), plappern (chatter), Rüsttag (day of preparation), Rüstzeug (tools), in Schafskleidern (in sheep's clothings), Schaubrot (unleavened bread), störrisch (stubborn, obstinate), überschattet (darkened, shadowed), übertüncht (whitewashed), verdolmetscht (interpreted, translated), wetterwendisch (capricious), Zinsgroschen (payment of interest), zermalmen (crush)

(nach: Joh. ERBEN, Luther und die deutsche Schriftsprache. In: Dt. Wortgeschichte I, 439-492)

Simultaneously, at the beginning of the 16th century, a third variant of written German originated, the Viennese Kanzleisprache or Gemeines Deutsch which was used in the court of the emperor Maximilian I (1493-1519). Had this variant become normative we would, in our days, speak and write a sort of Bavarian, i.e. paur instead of Bauer (peasant) or we would say Grüß Gott instead of Guten Tag or Hallo when meeting outside our homes.

In the course of its further development the New High German lingua franca which we know only in its written form underwent numerous changes and was used in jurisdiction and as a literary language, too. 1521 The reformer Ulrich von Hutten declares believing in a "Teutsch nation in ihrer sprach", 1526-1528 the famous Paracelsus gives his Basel lectures in German, 1525 Albrecht Dürer's geometrical reference book "Unterweisung der Messung" (instruction on the art of measuring) appears. In his "Orbis pictus" (1658) Johann Amos Comenius (1592-1670) the German language shows as understandable as could be accepted for didactical use.

Thus, at the end, a regional variant had become normative and, so to speak, the mother of our present-day standard German. On the other hand, each of the competing variants hypothetically could have been chosen as standard. So we could ask ourselves whether to regard the German dialects as autonomous, independent and even productive systems or, merely, as subordinate and thus less important ones. Often dialects are regarded as an inferior type of language restricted to lower-class people, which is as arrogant as stupid because, as we shall see, most of the dialects developed an ambitious literature with prose texts and poetry.

The dialect variety

"In the German linguistic area there is probably not a village or even a hamlet which is not in some way linguistically differentiated from its neighbours. It has been shown that even within a small isolated village there is no linguistic uniformity. There are differences between the generations, the sexes and individual families in the smallest isolated speech community."

R.E. KELLER, German Dialects, Manchester 1961, p.11

Besides the ptk-shift there are many other reasons why dialects were formed with distinctive features such as individual phonation, inflection, word-formation, phraseology and / or syntax. Basically there is a cross-relationship between linguistic development and territorial history. The large German-speaking area is divided into many sub-areas as you have a lot of rivers, lakes, mountains and other geographical obstacles forming natural boundaries and thus creating fenced-in places with their own population, culture and vernacular. Territories like that were often ruled by local gentry such as counts or princes who told their people even what sort of religious confession they had to follow. Culture and language developed individually in those regions. In the aera of feudalism hundreds of independent midget territories ("Kleinstaaterei") were founded as isolated zones of life, trade, and communication. In the middle of the 17th century, there were about 300 independent political regions in Germany which meant that, when traveling a considerable low distance, you had to cross at least several borders, pay toll etc. and that you could find individual variants of spoken German in each of these little countries. Thus, a host of local dialects originated, developed further and were handed over to the following generations; a lot of those variants have survived and are still used in domestic life or industrial work where people can use their vernacular to discuss problems of all sorts; dialect here becomes a language of solidarity.

One very interesting feature of German dialects is the so-called shibboleth, a Hebrew word meaning 'sign of recognition'. The shibboleth is one single word or phonetic sequence which gives you a clue to what type of dialect (and cultural context) is dealt with. It is amazing that you can recognize a dialect by hearing only one special word or sound. Here are some well-known shibboleths.

| [dialect] "Mää honns, mää konns, mää fahren met der Fulle übern Schdonz" |

| [standard] "Wir haben es, wir können es, wir fahren

mit der Fulda über den Badezuber" [English] "We've got it, we can do, we sail up the tub with the Fulda river" (instead of vice-versa). |

Another Kassel saying runs as follows:

| [d.] "Heert de Ridde dää? Nee, mää. Na, dann loss'n moo gauzen." |

| [st.] "Gehört der Rüde (=Hund) dir? Nein, mir.

Na, dann lass ihn mal bellen." [E.] "Does that dog belong to you? No, he is mine. OK, then let him bark." |

Some phenomena such as gutturalization in wing for 'wine' or palatalization of initial /k-/ in tchinner 'children' can be found in more than one dialect region which may be explained by the fact that settlers or merchants took their language with them when moving to distant regions.

Contrary

to

the German standard many dialects have individual words and

phrases for expressing emotions such as fear, joy, love or

hatred, for cursing or declarating love. Dialects

are mirrors of ethnicity, of regional culture and

feeling, and they correlate with the type of landscape,

too. The flatter it is the more monosyllabic words and less

phonetic resources you will find; the more mountains, lakes,

flowers there are the more types of sounds and inflection will be

in the respective regional and local dialects. There is a

so-called Mundartgefälle (decrease / increase of dialect

usage). The more south you go the more dialect is

spoken generally, even in the middle and even upper classes.

At the Eidgenössische

Technische Hochschule where Albert Einstein got his diploma you may come across

a lecture on nuclear physics in Swiss German phonation which is a

strong piece of evidence of how regional variants act in ethnic

identification.

Contrary

to

the German standard many dialects have individual words and

phrases for expressing emotions such as fear, joy, love or

hatred, for cursing or declarating love. Dialects

are mirrors of ethnicity, of regional culture and

feeling, and they correlate with the type of landscape,

too. The flatter it is the more monosyllabic words and less

phonetic resources you will find; the more mountains, lakes,

flowers there are the more types of sounds and inflection will be

in the respective regional and local dialects. There is a

so-called Mundartgefälle (decrease / increase of dialect

usage). The more south you go the more dialect is

spoken generally, even in the middle and even upper classes.

At the Eidgenössische

Technische Hochschule where Albert Einstein got his diploma you may come across

a lecture on nuclear physics in Swiss German phonation which is a

strong piece of evidence of how regional variants act in ethnic

identification.

If you want a more recent example please listen to helicopter

pilot Christian von Almen (see screenshot on the right) when, in ZDF "Abenteuer Wissen" (the adventure of

knowledge") on February 8th, 2006, he describes

his difficult job of hoisting heavy loads such as a 5 ton TV

antenna tower to the top of a 200-m-high chimney in Swiss German

phonation.

| "Also es ist Millimeterarbeit, die wir da machen; man

hat gar keinen Spielraum; bis tausend Kilo ist es

einfacher, da können die Leute unten helfen, und bei fünf

Tonnen, da können sie nicht mehr viel helfen; sie können

ein bißchen stabilisieren, aber sie können die Last nicht

mehr ziehen und so, da muß man alles ziemlich selber

machen." "Well, it's a delicate piece of manoeuvring; there is no tolerance; up to 1.000 kilos it is easier and people down there can help, but with 5 tons they can't help any longer, they can only stabilize the load, they can't tow it and so you rather have to do all of that yourself." |

Changes are everywhere

As we have seen a linguistic variant becomes normative as soon as it succeeds in bringing about generally-accepted conventions. The new-born standard keeps being adjusted according to changing times with their individual innovations and challenges. Here one might conclude that the dialects tend to remain static because they aren't used generally by a large speech community in multiple situations. While in foreign-country linguistic enclaves, the Sprachinseln, dialects and culture have remained conservative there are changes in many local German dialects. Here you find a lot of linguistic contacts with neighbouring communities, and new family members coming from distant areas import their words and phrases which are implanted in the local dialect. Sometimes, the local dialect is learned as a target language by talented speakers such as Karl Trust who I met in January this year. Having grown up in Sarrebruck and learned its dialect, he later on went to Central Hessian Willershausen, a tiny village the dialect of which he then acquired up to perfection. You can hear this when he says Wenker phrase No. 16 in both dialects: [1] 35119 Rosenthal-Willershausen (Low Hessian / Rhine Franconian) [2] Saarbrücken (Saar dialect).

To a certain extent dialects get normatized too, when establishing themselves as a means of expressing identity. Identity bases on clearly definable facts and features otherwise a dialect speaker would be unable to say that someone is coming from a neighbouring village and thus no member of his own community. He can do so because he knows the distinctive features of his very own dialect, and that is enough. While standard continuously gets refined and keeps adopting neologisms the dialects too get modified; they have to find names or phonetic equivalents for cultural innovations just as the young people innovate their specific language which tends to change every decade.

[K.H. KÄSINGER on "Dialect at school" in Hessian Schwalm dialect, May 2001]. Experienced teachers believe that people mastering and clearly discerning two variants do not make as many mistakes as those using a sort of mixed type of language containing elements of standard and regional German. In present-day Germany lots of young people carelessly using anglicisms are no longer able to read ambitious texts with words and phrases which are too "German" to be understood.

As far as the awareness of German dialects is concerned

we find a famous passage as early as 1300 when Hugo von Trimberg (ca. 1235-1313), a

Franconian poet and teacher, first mentions lantsprâchen, i.e.

areal languages, which is practically the first German

expression for Mundarten. His didactical epic poem "Der Renner" (containing 24.611 verses) is one

of the comprehensive encyclopaedic works following the tradition

to sum up the knowledge of that time. Knowing human nature, Hugo

allegorically castigates the seven cardinal sins and criticizes

the estates of his time, accusing the nobility of

arrogance and luxury and saying that the clergy was as

greedy as ignorant. Despising knighthood and courtly life, he

feels sympathetic with the poor who have no rights. The author's

high regard of his origin and dialect conveys a certain feeling of

solidarity which may be one reason why the "Renner" was copied

many times even in Hugo's lifetime, thus spreading forward and

gaining popularity. Let us see what Hugo writes about areal

languages:

| Von manigerlei sprâche

22261 An sprâche, an mâze und an gewande 22265 Swâben ir wörter spaltent, |

On various languages

As far as languages, measures and clothing are

concerned The Swabians split their words, |

Babenberger here: 'people from Bamberg; Swanfeld Schwanfeld (district of Schweinfurt; where Walther von der Vogelweide is said to have lived)

In lines 22299 ff. Hugo describes his own Franconian dialect; as to the rest we have to guess what he wants to tell us; on the other hand, here we have the first attempt to characterize dialects and to allocate them to their speakers.

Another

dialect which is not mentioned here played an enormous role even

in early texts and the history of dialects. The Cuxhaven garden

stone on the left-hand side shows you all the important

characteristics of Low

German. "Do what you want (or: whatever you do) people keep

talking". Up to the present, snacken has been a typical LG

expression for talk or chat; we can find it as

early as in the 13th century when, in his Meier Helmbrecht,

Wernher der Gaertenaere uses LG elements to

characterize what he regards as the language of the simple-minded,

naive person, the dorpaere (the origin of NHG Tölpel

'fool'), that is someone living in a village and unable to get

higher-level education. On the other hand such a characterization

is injust because, as the following sample shows, Low German was

then used for writing official documents:

Another

dialect which is not mentioned here played an enormous role even

in early texts and the history of dialects. The Cuxhaven garden

stone on the left-hand side shows you all the important

characteristics of Low

German. "Do what you want (or: whatever you do) people keep

talking". Up to the present, snacken has been a typical LG

expression for talk or chat; we can find it as

early as in the 13th century when, in his Meier Helmbrecht,

Wernher der Gaertenaere uses LG elements to

characterize what he regards as the language of the simple-minded,

naive person, the dorpaere (the origin of NHG Tölpel

'fool'), that is someone living in a village and unable to get

higher-level education. On the other hand such a characterization

is injust because, as the following sample shows, Low German was

then used for writing official documents:

"Wi Ropraght (...) bekennen vnde don / kunt / allen die dessen bref sien vnde horen lesen dat wi hebbet ghelouet vnde louen in dessen ghyghenwarden breue / dat wi (...) maket vnde kundyghen (...) / Desse bref is ghegheuen / des gude(n)daghes vor Sante vrbanes daghe in den iare also man tellet van godes ghebort dusent drihu(n)dert vnde eyne(n)twintygh iar"

In 1652 the professor of mathematics and poetry and linguistic purist Johann Lauremberg (1590-1658) is very self-assured in practicing Low German when he praises his Mecklenburg vernacular in the following lines "Van alemodischer Poesie und Rimen" (on fashionable poetry and rhyming; I leave this document to you for further studies):

|

||||

In the last decades Low German encountered a sort of revival and brought about a new feeling of identity throughout the northern German speaking territories. As I stated earlier there are newscasts in Plattdeutsch and there is a Low German issue of the Wikipedia which introduces itself as follows:

"De Wikipedia is en free Nokieksel in mehr as 100 Spraken, wo jedereen an mitwarken kann. Man to! Schriev rin, wenn du wat weetst. Kiek na bi de Infos för Niege un bi Hülp. Siet April 2003 is de plattdüütsche Utgaav vun de Wikipedia an't Wassen un hett in dissen Momang 2.114 Artikels. Alle Artikels staht ünner de GNU-Lizenz för fre'e Dokumentatschoon." "The Wikipedia is a free encyclopedia in more than 100 languages to which everyone can contribute. Off you go! Write in what you know. Look up the infos for newcomers and on help. Since April 2003 the Low German issue of the Wikipedia is growing and, in this moment, contains 2.114 articles all of which are distributed under the GNU free documentation license."

Dialects in literature and poetry

Entering that special subject I should like to refer to Jazz. This form of musical expression originated around 1900 in the New Orleans area. Similar to many dialects it first served as a vehicle for articulating all sorts of concern among the black people there. Later on this musical vernacular developed branching out into several style variants. There was a similar development towards literature and styles when dialect was used to write down all sorts of emotions and thoughts, ranging from traditional rural idyll to new creative forms of expression. Fritz Reuter (1810-1874), Klaus Groth (1819-1899) and Ludwig Thoma (1867-1921) belong to the most excellent dialect poets around 1900.

In our first example Klaus Groth glorifies his mother tongue; the text was written on Fehmarn island (in the Baltic Sea). Trying to preserve metrics, I translated it into standard German (in 1996) and into English (just for this lecture).

| Min Modersprak, wa klingst du schön! Wa büst du mi vertrut! Weer ok min Hart as Stahl un Steen, Du drevst den Stolt herut. Du bögst min stiwe Nack so licht Ik föhl mi as en lüttjet Kind, Min Obbe folt mi noch de Hann' Un föhl so deep: dat ward verstan, Min Modersprak, so slicht un recht, So herrli klingt mi keen Musik |

O Muttersprache, klingst du rein! Wie bist du mir vertraut! Wär' auch mein Herz wie Stahl und Stein, Du triebst den Stolz heraus. Du beugst den steifen Hals so leicht Ich fühl mich wie ein kleines Kind, Großvater faltet mir die Hand Die Rede wirkt, schenkt neuen Mut, O Muttersprache, recht und schlicht, So herrlich klingt keine Musik, |

My mother tongue, you sound so clear, I know you from my start, And even with a heart of steal I'd lose my pride at last So easily you bend my neck You make me feel a little child My grandpa folds my very hands It is so deep, I understood, My mother tongue, so plain and true, No music is as wonderful |

In the second half of the 20th century we have Herbert Achternbusch (*1938, Upper Bavarian), Dieter Bellmann (*1930) and Walter A Kreye (Low German), Franz Xaver Kroetz (Bavarian), Peter Kuhweide (Westphalian), Kurt Sigel (* 1931, Frankfurt Hessian), Ludwig Soumagne (Low Rhenish Ripuarian), André Weckmann (Low Alsatian) and others.

The following samples were taken from: BOSCH, Manfred (ed.): Mundartliteratur. Frankfurt u.a. 1979, each one given with its standard German and English equivalent (by me). Contrary to former idyllic description poetry now emancipates as a tool of social criticism as can be seen first in the few Swabian lines Georg Holzwarth (*1943) writes on the German saying "Von nichts kommt nichts" (you don't get anything without effort):

| Wenn e sauf no wer e bsoffa wenn e schaff no wer e miad ond wenn e gar nex dua no schlof e ei aber von was kommt bloß mei Wuat dui Sauwuat |

Wenn ich sauf dann werd ich besoffen wenn ich schaff dann werd ich müd und wenn ich gar nichts tu dann schlaf ich ein aber wovon kommt bloß meine Wut die Sauwut |

When I drink I get stocious when I work I get tired and when I don't do anything I fall asleep but what the hell is the cause of my rage of my bloody damn rage |

Eberhard Wagner (* 1938) writes his notions on men's work in Bayreuth Franconian:

| 1 die ärwad is ka fruusch sie hubfd da ned davoo 2 fang nix oo dann braugsd nix aufheern 3 a ärwad muß ihr geld werd saa owa kan bfenning driewa 4 mei ärwad und miich uns zwaa schbannd as geld zam wie as woochscheid die ogsn 5 wer schufdn dud auf mord und exbress der muß damid rächna daßa im grund auf mord und kabudd schufdn dud 6 wenn die ärwad amoll schdärbd noch geh i auf ihr leich und kaaf ara an schensdn gronz 7 za duud gärwad is aa gschdorm |

1 die Arbeit ist kein Frosch sie hüpft dir nicht davon 2 fang nichts an dann brauchst du nichts aufzuhören 3 eine Arbeit muß ihr Geld wert sein aber keinen Pfennig mehr 4 meine Arbeit und mich uns zwei spannt das Geld zusammen wie das Waagscheit die Ochsen 5 wer schuftet auf Teufel komm raus im Akkord der muß damit rechnen daß er im Grunde auf Teufel komm raus sich kaputt schuftet 6 wenn die Arbeit mal stirbt dann geh ich zu ihrer Beerdigung und kauf ihr den schönsten Kranz 7 sich zu Tode gearbeitet ist auch gestorben |

1 work is no frog it doesn't leap away 2 don't start anything so you mustn't stop anything 3 work must be worth hard cash down to the last penny 4 my work and me money ties us together as the bar does with the oxen 5 whoever slogs away in a murderous haste has to reckon with the simple fact that he works himself to death 6 when work happens to die I join its burial Laying down the most beautiful wreath 7 having slogged to death is a way of dying, too |

The Dreiländereck (Dreyeckland) unites German, Swiss and French speakers in their Alemannic dialect which, here, becomes a vehicle of protest against environmental pollution and nuclear power stations. Let us hear André Weckmann's Ringold (Rhine Gold, in Alsatian Alemannic), the "three gentlemen" mentioned there represent the three respective countries polluting nature and running nukes:

| Es hucke drej Herre am Rhin un speele Ruhr uf Franzeesch un uf Ditsch, metme Zaichebrätt dr Aant met Millioneschecks de Zwait met Gummiknettel de Drett Es hucke drej Herre am Rhin Es brunze drej Herre am Rhin |

Es hocken drei Herren am Rhein und spielen Ruhrgebiet auf Französisch und auf Deutsch, am Reißbrett der erste, mit Millionenschecks der zweite, mit Gummiknüppeln der dritte. Es hocken drei Herren am Rhein, Es pinkeln drei Herren am Rhein Es spalten drei Herren am Rhein |

Three gentlemen sit at the Rhine playing Ruhr in the French and in the German way, with a drawing board the first, with million dollar cheques the second with truncheons the third Three gentlemen sit at the Rhine Three gentlemen pee at the Rhine |

Finally a sample of dialect prose. Ulla Hahn (* 1946) who grew up in the Rhine

area, studied German philology and finally was promoted PhD,

thoroughly demonstrates the Rhenish dialect of Dondorf ("Dondörp",

near Cologne) in her debut novel "Das verborgene Wort" (the hidden word). Let

me quote one of the numerous passages (p. 479 f.):

| "Nä (...), dat Heldejaad met singe Kamelle. Hür leever ens, wat dat Alma us verzällt hätt. En Röppresch hät sesch de Frau vom Dokter ömjebrät. Met Jeff. Mit Gift. Vürher hät dat Minsch dä ärme Kääl, dä Dokter, noh Strisch un Fade bedrore, und dobei noch Schulde jemaat, in de Zischtausende. Dann han se däm de janze Bud leerjerömp. Met däm Jerischtsvollzieher. Övverall dä Kuckuck drop. Un dann ab dursch de Mitte." (...) Dat Minsch wor schläät. Juut, dat et duut es. Un se han et och noch nit ens rischtisch bejrave. Et litt bei de Evanjelische in dä Eck für de Jlaubenslosen. | Nein, die Hildegard mit ihren Geschichten. Hör lieber mal, was die Alma uns erzählt hat. In Rüpprich hat sich die Arztfrau umgebracht. Mit Gift. Vorher hat die Schlampe den armen Kerl, den Doktor, nach Strich und Faden betrogen und dabei noch Schulden gemacht, in die -zigtausende. Dann haben sie dem die ganze Bude leergeräumt. Mit dem Gerichtsvollzieher. Überall den Kuckuck drauf. Und dann ab durch die Mitte. (...) Das Mensch war schlecht. Gut, daß sie tot ist. Und sie haben sie auch noch nicht mal richtig begraben. Sie liegt bei den Evangelischen in der Ecke für die Ungläubigen. | Oh boy, Hildegard with her stories. Let's hear what Alma told us. In Rupprich the doctor's wife killed herself. With poison. Before that this slut had often cuckolded the doctor, the poor chap, running up a lot of debts up to ten thousands. Then they cleared his apartment, took away everything, with a bailiff putting his seal everywhere, and off they went. (...) What an evil woman she was. Thank heavens she's dead. And they even didn't bury her decently. She is with the protestants, in the disbelievers' corner. |

Our last sample shows that in vocal music, too, dialect may act as a mouthpiece of lower social classes. So, in 1742, Christian Friedrich Henrici (called Picander) uses part of Saxonian dialect in his libretto of Johann Sebastian Bach's Bauernkantate (peasants' cantata) BWV 212 where a vocal duetto opens singing "Mer hahn en neue Oberkeet" (which I recorded on May 1st, 2k4 in the new Bachhaus of Bad Hersfeld)

Mer hahn en neue Oberkeet

An unsern Kammerherrn.

Ha(r) gibt uns Bier, das steigt ins Heet,

Das ist der klare Kern.

Der Pfarr' mag immer böse tun;

Ihr Speelleut, halt' euch flink!

Der Kittel wackelt Mieken schun,

Das klene luse Ding.Wir haben eine neue Obrigkeit

In unserem Kammerherrn.

Er gibt uns Bier, das steigt ins Haupt,

Das ist der klare Kern.

Der Pfarrer mag immer böse tun,

Ihr Spielleut', seid bereit!

Der Kittel wackelt der Mieke schon,

Das kleine lose Ding.We've been given a new master now,

It's our Chamberlain.

He gives us beer, we're happy then,

That is the real thing.

The parson may be cross at length

Musicians, be prepared!

And Mieke's smock is shaking now,

Lo that tiny cheeky thing.

Dialect portrays local people in Ludwig Thoma's one-act-play "Erster Klasse" and the working class in Gerhart Hauptmann's "Die Weber" (1893). In Jürgen von Mangers and Jochen Steffen's sketches regional Umgangssprachen (Ruhrdeutsch, North German Missingsch) serve as sociolects. Dialect may also function as a means of alienation (Verfremdung). In his cabaret scenes, Emil Steinberger uses Swiss German dialect words and sounds as a tool of comedy. Here transphonation is used to evoke comical effects. The very famous British TV sitcom "Allo-allo" shows an extreme form of transphonation when police officer Crabtree who "only thinks he speaks French" bids hallo saying "Good Moaning" and produces phrases like "I have good nose" ('news'), "my mither-in-loo" ('mother-in-law'), "the bitteries for the rodeo" ('the batteries for the radio') or "they are farting for freedom" ('fighting ...').

More on language history and dialect as targets of science

Hugo's "Renner" of 1300 mentions regional variants without claiming to be scientific. When Martin Luther made his Bible translations his "Sendbrief" reflects on phenomena and principles of transforming one language to another. When his thoughts spread wide and people in some regions could not understand specific utterances there was the need for glossaries which could help. 1532 Adam Petri's glossary for Luther's NT translation appeared, 1555 Konrad Gesner published a Swabian-Swiss German word list, and the 17th century gave birth to many so-called Idiotica , i.e. regional dialect dictionaries. In the first half of the 19th century comprehensive anthologies appeared and Johann Andreas Schmeller's "Karte der Mundarten Bayerns" (1821) marked the beginning of what was called linguistic geography (time table see here and here). We owe to this scientific branch nearly all we know about the existence and typology of the regional and local German dialects. Linguistic geography is the art of showing variation of any kind (regarding phonetics, morphology, vocabulary, phraseology, syntax) in defined locations within a geographic mesh or net. Normally a neutral map serves as a basic layer; it contains all locations in question which are then marked according to the individual data found there. If optimally laid out this map can show, even at first sight, variation constituting what you can call a dialect. On the other hand it may be difficult to set waypoints for every language or dialect in question. As any sort of variation can be demonstrated on maps the term "thematic geography" was created. If skilfully designed, those maps are well apt for didactic purposes in all fields of education.

While Karl Bernhardi's "Sprachkarte von Deutschland" of 1843 represents a second prototype of linguistic geography it was 25-year-old philologist and elementary teacher Georg Wenker who, in his article on the Rhenish Platt (1877), demonstrated his stunning knowledge on all kinds of and variations in the local dialects of the large Rhine Province. Wenker wanted to systematically explore the Rhenish dialects referring to whether they obeyed the phonetic laws which had been established by the so-called Junggrammatiker (New Grammarians). For this he invented a set of 40 standardized phrases containing all relevant phenomena regarding phonation and morphology where variation of any kind could be expected. Here are some of these Wenker phrases together with their Dutch and English equivalents:

1. D Im Winter fliegen

die trockenen Blätter in der Luft herum.

==> new: text-aloud reading

(3.4.2k8)

NL In de winter vliegen

de droge bladeren door de lucht.

E In winter the dry

leaves are flying around in the

air.

2. Es hört gleich auf zu schneien,

dann wird das Wetter wieder besser.

Het houdt straks op te sneeuwen,

dan wordt het weer weer beter.

It will stop snowing

soon, then the weather will get better.

3. Tu Kohlen in den Ofen,

damit die Milch bald zu kochen anfängt.

Doe kolen op de

kachel, dat de melk gauw begint te koken.

Put coals in the

oven (so) that the milk will start boiling

soon.

7. Er ißt die Eier

immer ohne Salz und Pfeffer.

Hij eet de eieren

steeds zonder zout en peper.

He always eats

the eggs without salt

and pepper.

16. Du bist noch nicht groß

genug, um eine Flasche Wein

allein auszutrinken, du mußt erst

noch wachsen und größer werden.

Jij bent nog niet

groot genoeg om een fles wijn leeg te drinken, je moet

eerst nog een beetje groeien

en groter worden.

You aren't

tall enough yet to empty a bottle of wine;

you have to grow a bit and get taller first.

In the framework of the Deutsche Sprachatlas or other

projects these Wenker phrases (vocabulary see here) have been used up

to the present day; thus serving as a tertium comparationis, a common base for

comparing linguistic variants. Our phrase No. 16 will  be

used later on to demonstrate the sound of variants in the main

German-speaking areas. Regarding, as the Junggrammatiker

did, the German language as a "Germanic dialect" and using English

as a reference system we can compare the real German dialects with

the English language because most of them are closely related to

it, not only in the sense of phonetics but also with regard to

vocabulary and syntax. So a person who does not know German or can

hardly understand its standard will be able to understand at least

part of its dialects.

be

used later on to demonstrate the sound of variants in the main

German-speaking areas. Regarding, as the Junggrammatiker

did, the German language as a "Germanic dialect" and using English

as a reference system we can compare the real German dialects with

the English language because most of them are closely related to

it, not only in the sense of phonetics but also with regard to

vocabulary and syntax. So a person who does not know German or can

hardly understand its standard will be able to understand at least

part of its dialects.

Drawing his Sprachatlas der Rheinprovinz Wenker discovered two phenomena: 1. there was no uniform sound shift in all sub-areas (as is shown in the "Rhenish Fan", see right, taken from LOEFFLER, Probleme der Dialektologie, S. 28), 2. dialects differ not only with regard to phonation but also as far as morphology, vocabulary, phraseology and sometimes also syntax are concerned. Further studies on areal diversity produced a lot of impressive examples in these fields such as Gaul (from french cheval), Hengst (a Frisian word), Roß (with inverted /r/ in engl. horse), Mähre (engl. mare) and others for "Pferd" (which comes from Middle Latin paraveredus 'battle horse') or, as the German Word Atlas showed, a lot of lexical variants for "Ameise" (ant). In his Word Atlas (Wortatlas der deutschen Umgangssprachen. Bd. I/II [1977/78] III [1993], IV [2000]) Jürgen Eichhoff showed that similar differences can be also detected in the German Umgangssprachen.

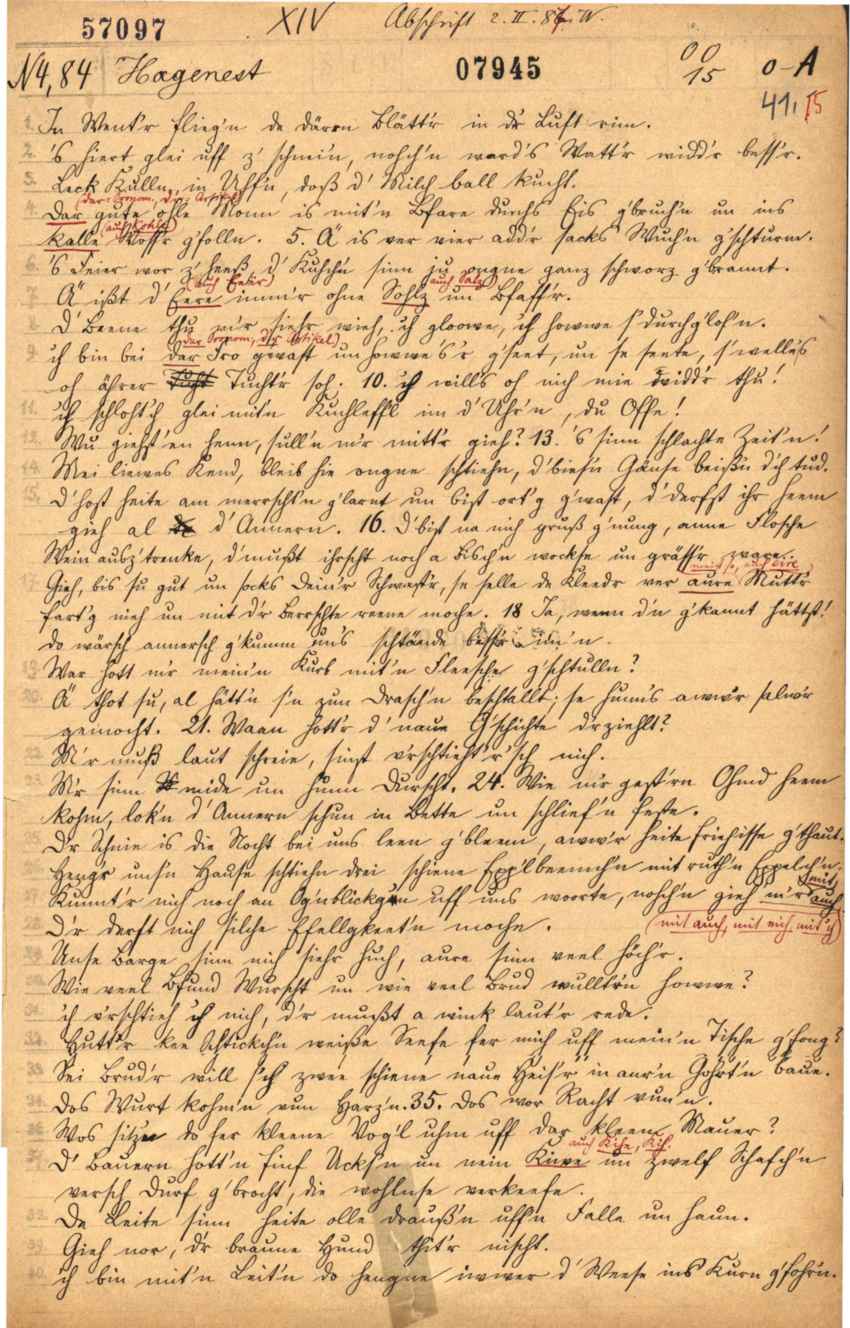

Wenker sent his questionnaire to every location, asking the

teacher in question to translate, with the help of his pupils, the

phrases into the local dialect. On page 2 the teacher was asked to

give his personal data and to answer some questions referring to

special words and traditions in his location. As we can conclude

from the above questionnaire of Borna

near Leipzig 1. most of the sheets were filled out in an old

handwriting called Sütterlin, 2. the research area later on

comprised all of the German speaking territory, which meant that

at last more than 40.000 questionnaires had to be evaluated;

neither Georg Wenker (who died in 1911) nor his successors (Wrede, Mitzka, Schmitt)

could complete this task. About 1.500 coloured maps were painted

of which only 128 could be printed from 1927 to 1956. Wenker's

method uses an indirect way of data retrieval, that means

he did not visit the dialect speakers, he did not question them

personally, he could not carefully listen to their pronunciation

and write it down in a phonetic transcription. So 1. there was no

inter-action between the explorer and the speakers, 2. the

relevant details of local variants were not given in phonetic

notation but only in a sort of standardized written

German. This way of data retrieval was subject to severe

criticism. 120 years later Juergen Schmidt and his team created

the Digitale

Wenkeratlas. Comparing Wenker's findings with modern data

they soon found out that the Sprachatlas questionnaires

produced much more exactitude in documentation than had been

maintained by the critics.  The Deutsche Sprachatlas

is the only linguistic atlas documenting data of each and every

individual location where German is spoken and taught. As the

first and foremost example it finally served as a model of

linguistic geography; dialect atlases were published all over the

world; in Japan, a most intensive research on dialects was

initiated. The first linguistic atlas in two volumes (phonology

and morphology) appeared as early as 1905–06. The Cercle

dialectologique du Japon, the Nihon

Gengo-Chizu (Linguistic Atlas of Japan, Tokyo

1966-1974), the Grammar Atlas of Japanese

dialects (GAJ), and the Corpus of Spontaneous Japanese (CSJ,

1999-2003) follow this tradition which led to innovative

methods such as the System of Exhibition and Analysis of

Linguistic Data (SEAL).

The Deutsche Sprachatlas

is the only linguistic atlas documenting data of each and every

individual location where German is spoken and taught. As the

first and foremost example it finally served as a model of

linguistic geography; dialect atlases were published all over the

world; in Japan, a most intensive research on dialects was

initiated. The first linguistic atlas in two volumes (phonology

and morphology) appeared as early as 1905–06. The Cercle

dialectologique du Japon, the Nihon

Gengo-Chizu (Linguistic Atlas of Japan, Tokyo

1966-1974), the Grammar Atlas of Japanese

dialects (GAJ), and the Corpus of Spontaneous Japanese (CSJ,

1999-2003) follow this tradition which led to innovative

methods such as the System of Exhibition and Analysis of

Linguistic Data (SEAL).

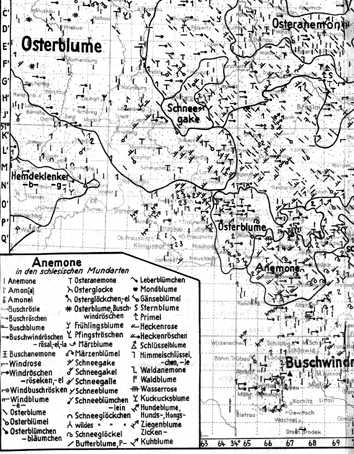

Walther Mitzka's Deutscher Wortatlas (part of map "Anemone" on the right) is equally ambitious and comprehensive; initiated in 1939, it was published in 22 vols up to 1980 and bases on 47.000 questionnaires which had been sent to the respective towns and villages (including German speaking Switzerland, Luxemburg the Netherlands) containing at least one institution where a teacher and his pupils could supply information with regard to lexical variety in the 200 words in question. One by-product of this research is a lot of phonetic variance which may be seen in the word lists. As the Sprachatlas the Word Atlas, too, was taken as an example for geolinguistic research (see bibliography and other related parts of my website).

The Sprachatlas and Wortatlas being too complicated, there was the need of creating a sort of handy instrument for showing the most striking differences in the German dialect landscape. So, in 1970, Werner H. Veith and Wolfgang Putschke decided to create the so-called Kleiner Deutscher Sprachatlas which bases on 6.000 reference locations the data of which were computationally analyzed and processed by Veith and his team so that Vols. 1.1, 1.2, 2.1 and 2.2 could be published from 1984 to 1999.

At the beginning of the 21th century we have, at last, the

technical resources needed for scanning and printing Wenker's

large multi-colour hand-painted dialect maps and for uploading

them into the Internet to make them known world-wide. Initiated by

Jürgen Erich Schmidt in 2000 and processed in

a special geographic

information laboratory, the Digital Wenker Atlas

now comprises one Terabyte of data and is regarded as the

most significant and voluminous contemporary project of linguistic

geography. As far as sound recordings are available they

will be integrated into the project, each Wenker phrase being

tagged into sub-units so that phrases or parts of them can be

selected. Each location being correctly positioned, the DiWA is a

high-precision work of geodatics, thus enabling other thematical

maps to be overlayed. With Wenker's data the DiWA documents a synchronic

stage of linguistic development which may be contrasted to

recent data and thus show diachronic trends and contrasts.

(Lit.: Eckhard Eggers (ed.): Moderne Dialekte, neue Dialektologie:

Akten des 1. Kongresses der Internationalen

Gesellschaft für Dialektologie des Deutschen (IGDD) am Forschungsinstitut für deutsche Sprache

"Deutscher Sprachatlas" der Philipps-Universität Marburg vom

5. - 8. März 2003 [Modern Dialects - Modern Dialectology:

Proceedings of the First Congress of the International Society of

German Dialectology, 5th to 8th March 2003, at the Research

Institute for German Language "Deutscher Sprachatlas" at

Philipps-Universitaet Marburg]. Stuttgart 2005)

The acoustical approach

"As far as regions are concerned Germans differ in the tempo of speaking, in dynamics and musical accents" (Die landschaftliche Wesensart deutscher Menschen äußert sich etwa in dem hier und dort verschiedenen Tempo der Rede, im dynamischen und musikalischen Akzent)

Adolf Bach, Deutsche Mundartforschung, 3. Aufl. Heidelberg 1969, p. 288

Whereas written documentation (see my transcriptions) shows phonematically and morphologically relevant dialect structures even the most precise API transcription is unable to demonstrate a dialect unless a competent native speaker transforms the written "score" into adequate phonation. Individual speech bases on normally unwritten data called suprasegmentals, i.e. stress, force of articulation, pitch and intonation which altogether constitute the prosody of speech. You know the falling and rising tune in English sentences and you further know the important rule of pitch or tone in Chinese. If you get familiar with German dialects these prosodic data will signalize where an individual speaker is to be located, for, as you can hear in our samples, every region has its individual intonation scheme which may serve as shibboleth.

One example of regional intonation is the so-called "Rheinische Schärfung" (see here; a term meaning a specially singing way of speech, KELLER calls it correption, in the Öcher Platt, the Aachen dialect, it means a short delay before a voiceless double consonant e.g. za-ppe, po-che) which you hear in the recording of Rath Heumar (Porz am Rhein, K'9,4+9) which was made in 1936 for the "Lautdenkmal reichsdeutscher Mundarten".

Speech and music

Speech and music have a lot in common evidence of which can be found in numerous 'musical' sayings and expressions enriching the German language. Der Ton, is said, macht die Musik which means that you have to play the exact notes when performing in a concert or, as often translated, it's not what you say but how you say it. The way of producing a linguistic utterance is what constitutes an individual dialect. The way of speaking, be it hectic, uncertain or balanced, generally serves as sort of fingerprint of the speaker's personality. We are used to be assessed from how we speak, especially in a situation where the other side cannot see the gestures and facial expressions underlining what we intend to convey when we communicate on the phone or to a blind person. What we say will then be accepted or rejected due to the vocabulary we use and due to the prosodic way, the tone, the accent, the melody of our utterance. The more dynamic and melodious we speak the more impressive this will be to the person who hears it.

It is the dialects which use all their phonetic and lexical instrumentarium to convey not only sober facts but also a whole range of emotions. This emotional competence, this tonal strength still makes them so impressive.

A few samples may demonstrate how dialectal speech may

correspond to musical variation. Let me first refer to Antonio Vivaldi's (1678-1741) concerto for

two violins and strings op. 3,8 (RV 522) from his cycle "L'estro armonico". The initial sequence of

the first movement is presented as a midi file which

tries to emulate how it may sound played by a harpsichord // or with higher speed:

The original baroque version for strings is performed

Our second sample is the

ouverture to Bach's Easter Oratory;

Our second sample is the

ouverture to Bach's Easter Oratory;

From that we can conclude:

We can use this when reflecting upon speech, especially dialect variation. A standard language Wenker phrase like

Du bist noch nicht groß genug, um eine Flasche Wein allein auszutrinken, du mußt erst noch wachsen und größer werden.

corresponds to our musical theme in its original notation as we heard it in the midi file. When we hear dialectal variants like

26789 Leer (East Frisia) or Mamer nr. Luxembourg (Luxemburgish,

Lëtzebuergesch)

we can analyze them using the above mentioned criteria [1a] to

[1c] where

1a) phrasing corresponds

with the suprasegmentals (stress, force of

articulation, pitch)

1b) instrumentation may

be compared to the phonological characteristics (dialect

phonation) and

1c) ornamentation with

the morphological features in word formation and

inflection

we have to add some phenomena which are not included in music:

1d) lexical variation

(e.g. Gaul / Roß / Mähre for Pferd)

1e) idiomatic variation

(e.g. do legst di nieder or do leckst mi am Orsch

for 'I am stunned')

1f) syntactical variation

(e.g.

gestern war ich in Darmstadt gewesen where the

south Hessian dialect uses past perfect instead of past

tense)

or: gestern habe

ich hier keinen Menschen nicht gesehen (double

negation such as in Bavarian)

Dialect samples

Here is our Wenker phrase No. 16:

We listen to the following samples, comparing them to their English

and Dutch equivalents which, as you will hear, have a

lot in common with the Low German dialect forms so that

you will be able to understand them even if you normally don't

understand German:

Comparing German, English and Dutch

Du bist noch nicht

groß genug, um eine Flasche Wein

allein auszutrinken, du mußt erst

noch wachsen und größer werden.

Jij bent nog niet

groot genoeg om een fles wijn leeg te drinken, je moet

eerst nog een beetje groeien

en groter worden.

You aren't

tall enough yet to empty a bottle of wine;

you have to grow a bit and get taller first.

we now hear the following samples:

Comparing German, English and Dutch

Du bist noch nicht

groß genug, um eine Flasche Wein

allein auszutrinken, du mußt erst

noch wachsen und größer werden.

Jij bent nog niet

groot genoeg om een fles wijn leeg te drinken, je moet

eerst nog een beetje groeien

en groter worden.

You aren't

tall enough yet to empty a bottle of wine;

you have to grow a bit and get taller first.

let us listen to our last samples:

Samples No. 3 and 7 were produced by persons who learned the dialect as a target (foreign) language

Our samples were to show how rich the arsenal of German dialects has been up to the present and how striking the differences are that can be heard. Let us sum up:

As for other data and findings please refer to my homepage. You will find historical samples of German dialects in the 1930's in the so-called Lautdenkmal reichsdeutscher Mundarten, a series of ca. 300 recordings which was neglected for decades but did not deserve that at all because it represents the first acoustical documentation of German dialects from all main regions in a technically acceptable sound quality. Though these recordings were made seventy years ago most of them sound pretty good especially when re-mastered with the help of computational methods and algorithms. This leads us to the last aspect of our talk, namely the question of how dialect samples can be generated and presented in a way affordable not only to research institutions but also to individuals using relatively modest equipment as I did with regard to the samples in my website.

When

Georg Wenker planned and started his Linguistic Atlas there wasn't

yet any equipment capable of recording speech in a way you could

clearly perceive or even present. Edison's phonograph, the "talking machine" of 1877,

could only record some low frequency sounds and the reproduction

was scratchy so you could hardly guess what had been recorded.

Even 25 years later there was no significant improvement which you

can realize listening to Austrian emperor Franz Joseph's recording of 1903. When

Wenker's successor Ferdinand Wrede had his memorable speech on Language and Nationality phonographed in

1926 some very important innovations were to appear. Sound

recording changed from mechanical to electrically

amplified processing and, in 1928, Georg Neumann invented his revolutionary condenser microphone which, from then

on, has been providing excellent full-range audio quality in all

possible cases. In 1935 the German firm AEG (Telefunken) presented

another innovation, the tape recorder which was optimized

in 1940 when Braunmühl and Weber invented pre-magnetization which enabled recording the

full audio spectrum on magnetic tape so that, in 1943, the German

Reichsrundfunkgesellschaft could carry out the first high

fidelity stereo recordings. As early as 1936 and 1937 the Lautdenkmal reichsdeutscher

Mundarten had been produced using the then most

sophisticated microphone

and gramophone recording equipment. In our days recording

speech does no longer need heavy and complicated equipment.

The little Sharp Minidisk recorder with the plug-in

electret condenser mike on the left is more than sufficient to do

this job as you could hear in my japanese samples which were

mastered with the help of my notebook. When you want to record

music or speech in stereo mode the so-called Jecklin

disk would be the best choice. It consists of a wooden disk

of ca. 25 cm in diameter and an omnidirectional ECM on either

side. With the home-made version on the right I could produce more

than 800 live recordings

on analogue and digital cassettes

ranging from chamber music to Mahler's 8th symphony

with over 350 performers. Stereophonic speech recording is the

perfect way of documenting dialects when you have speakers with

different variants and when you place them on either side of the

disk which helps decoding and differentiating their utterances.

When

Georg Wenker planned and started his Linguistic Atlas there wasn't

yet any equipment capable of recording speech in a way you could

clearly perceive or even present. Edison's phonograph, the "talking machine" of 1877,

could only record some low frequency sounds and the reproduction

was scratchy so you could hardly guess what had been recorded.

Even 25 years later there was no significant improvement which you

can realize listening to Austrian emperor Franz Joseph's recording of 1903. When

Wenker's successor Ferdinand Wrede had his memorable speech on Language and Nationality phonographed in

1926 some very important innovations were to appear. Sound

recording changed from mechanical to electrically

amplified processing and, in 1928, Georg Neumann invented his revolutionary condenser microphone which, from then

on, has been providing excellent full-range audio quality in all

possible cases. In 1935 the German firm AEG (Telefunken) presented

another innovation, the tape recorder which was optimized

in 1940 when Braunmühl and Weber invented pre-magnetization which enabled recording the

full audio spectrum on magnetic tape so that, in 1943, the German

Reichsrundfunkgesellschaft could carry out the first high

fidelity stereo recordings. As early as 1936 and 1937 the Lautdenkmal reichsdeutscher

Mundarten had been produced using the then most

sophisticated microphone

and gramophone recording equipment. In our days recording

speech does no longer need heavy and complicated equipment.

The little Sharp Minidisk recorder with the plug-in

electret condenser mike on the left is more than sufficient to do

this job as you could hear in my japanese samples which were

mastered with the help of my notebook. When you want to record

music or speech in stereo mode the so-called Jecklin

disk would be the best choice. It consists of a wooden disk

of ca. 25 cm in diameter and an omnidirectional ECM on either

side. With the home-made version on the right I could produce more

than 800 live recordings

on analogue and digital cassettes

ranging from chamber music to Mahler's 8th symphony

with over 350 performers. Stereophonic speech recording is the

perfect way of documenting dialects when you have speakers with

different variants and when you place them on either side of the

disk which helps decoding and differentiating their utterances.

To decode speech you must be able to perceive the formants of those consonants, vowels and diphthongs which constitute the meaning of a word or phrase. Generally we have to differentiate between acoustical (that is: organic) and mental perception. In the different stages of your hearing apparatus you perceive sound which, as an analogue signal, is then neurally conducted to a sort of black box where it is digitized and led to a part of the brain where it is decoded with a set of algorithms that we acquire and perfect in the course of our lifetime. Let us regard the sounds of /f/ and /s/ such as in the German minimal pair gereift / gereist (das Korn ist nun gereift 'ripened' / Herr Korn ist nun abgereist 'departed'). The Germans have no problems in differentiating between these two phonemena even if they are not reproduced in a technically sufficient way. The reason for that is that those practicing their maternal language use a sort of internal error correction based on linguistic competence. If a foreign language is concerned (which most of the German dialects will seem to be) you need all those distinctive formants otherwise some speech signals will be too misleading to be clearly interpreted. So when you demonstrate complex phonation sequences you have to use an equipment capable of reproducing a bandwidth containing room enough for all critical sounds and overtones which transport the message in question. In the case of speech a frequency range of about 200 to 4.000 Hertz may be sufficient which means that you can present your samples even with a considerably high rate of compression as it is used by algorithms like Real Audio, MP3, WMA and others. There are a lot of respective samples in my homepage. My collection Varieties of German offers 57 samples from all main German speaking areas in a compression rate of over 20; the resulting audio quality is, nevertheless, very near to the linear PCM recordings.

From the end of 1996 I made a lot of experiments with compression algorithms. Let me finally present to you a case of most extreme speech compression. Using a one-point stereo microphone I recorded the 40 Wenker phrases with a Central Hessian speaker on a SONY cassette tape recorder TCD-5M, then I transcoded the signal to mono and compressed it to Real Audio using a sampling frequency of only 5 kHz. That means a compression factor of around 280 where every recorded second needs only 600 Bytes to be realized. So all the 40 Wenker phrases are contained in only 133.300 Bytes (*.ra) resp. 215.496 Bytes (Fraunhofer *.mp3); when you hear them it sounds a bit narrow but you can still perceive all those phonetic features which constitute the Central Hessian Mundart of Großseelheim near Marburg, and that is, I think, a real achievement of sound compression and data processing.

So we are at the end of today's journey to the colourful landscape of German dialects. If there had not been those fascinating 1.300 years of German language history the dialects would not have emerged. Even nowadays, in our days of digitization, of computers, supersonic planes and aerospace you can hear a lot of dialects when traveling around Germany. These dialects are part of our history, part of our culture and our way of life. They are the linguistic garden of our culture with flowers of so many different sorts and origins. You can discover a lot and it will never be dull or boring to walk around here. It was my intention to only give you some modest impressions of that, and let me close with the hope that some sounds you heard to-day will keep ringing in your ears when I shall sit in a wonderful ANA plane on my way back to Germany. Sayonara.

Subject to change - all rights reserved.

c) W. Näser - rev.: 5.1.2025 (some links

corrected)